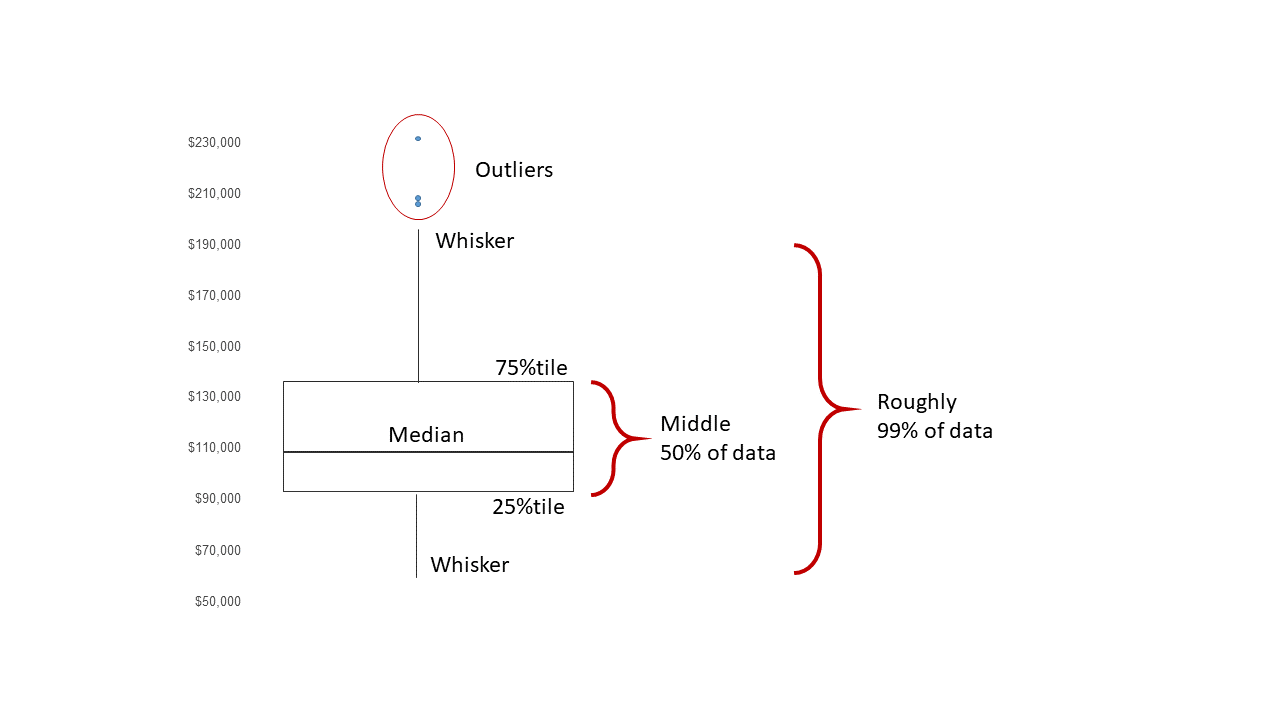

class: center, top, title-slide .title[ # Webinar 1 ] .subtitle[ ## Data Visualization ] .author[ ### Rogers Ochenge ] .date[ ### November 30, 2022<br>Updated: Dec 1, 2022 ] --- # Preamble -- + Opening Remarks- Introduction -- -- + **Inspiration**: International Summer School in Uganda: Survey Methodology and Data Management (ISSU),held at Muteesa I Royal University in Masaka, Uganda between 03-14 October 2022. The Summer School was funded by the VW Foundation and jointly organized by GESIS – Leibniz Institute for the Social Sciences, Germany, and Muteesa I Royal University, Uganda # Webinar Goal * Develop visualization skills in R --- # Univariate Graphs ## Categorical variables -- + The distribution of a single categorical variable is typically plotted with: 1. a bar chart, 2. a pie chart, or (less commonly) 3. a tree map. --- # Bar Charts: -- + The Marriage dataset contains the marriage records of 98 individuals in Mobile County, Alabama. Below, a bar chart is used to display the distribution of wedding participants by race. --- <!-- --> -- + The majority of participants are white, followed by black, with very few Hispanics or American Indians. --- -- + Percents -- -- + Bars can represent percents rather than counts. -- -- <!-- --> --- # Sorting categories + It is often helpful to sort the bars by frequency. --- -- --- -- <!-- --> --- # Pie Charts -- * Pie charts are controversial in statistics. -- -- * If your goal is to compare the frequency of categories, you are better off with bar charts (humans are better at judging the length of bars than the volume of pie slices). -- -- * If your goal is compare each category with the the whole (e.g., what portion of participants are Hispanic compared to all participants), and the number of categories is small, then pie charts may work for you. -- --- <!-- --> -- * The pie chart makes it easy to compare each slice with the whole. For example, Black is seen to roughly a quarter of the total participants. --- # Tree Map -- * In a treemap, each tile represents a single observation, with the area of the tile proportional to a variable. -- * Example: treemap with each tile representing a G-20 country. -- -- * The area of the tile will be mapped to the country’s GDP, and the tile’s fill colour mapped to its HDI (Human Development Index). -- -- <!-- --> --- # Subgrouping tiles -- * Let’s subgroup the countries by region -- -- <!-- --> --- # Quantitative -- * The distribution of a single quantitative variable is typically plotted with: -- -- 1. a histogram, -- -- 2. kernel density plot, or -- -- 3. dot plot. -- # Histogram -- * Using the Marriage dataset, let’s plot the ages of the wedding participants. --- -- <!-- --> -- * Most participants appear to be in their early 20’s with another group in their 40’s, and a much smaller group in their later sixties and early seventies. This would be a multimodal distribution. --- # Kernel Density plot -- * An alternative to a histogram is the kernel density plot. * Technically, kernel density estimation is a nonparametric method for estimating the probability density function of a continuous random variable. (What??) * Basically, we are trying to draw a smoothed histogram, where the area under the curve equals one. -- -- <!-- --> --- -- * Fill the density with color -- -- <!-- --> -- * The graph shows the distribution of scores. For example, the proportion of cases between 20 and 40 years old would be represented by the area under the curve between 20 and 40 on the x-axis. --- -- * Better still -- -- ``` ## [1] 5.181946 ``` <!-- --> -- * Kernel density plots allow you to easily see which scores are most frequent and which are relatively rare. -- -- * However it can be difficult to explain the meaning of the y-axis to a non-statistician. (But it will make you look really smart at parties!) --- # Dot Chart -- * Another alternative to the histogram is the **dot chart**. * Again, the quantitative variable is divided into bins, but rather than summary bars, each observation is represented by a dot. * By default, the width of a dot corresponds to the bin width, and dots are stacked, with each dot representing one observation. * This works best when the number of observations is small (say, less than 150). -- -- <!-- --> --- # Bivariate Graphs -- * Bivariate graphs display the relationship between two variables. The type of graph will depend on the measurement level of the variables (categorical or quantitative). -- * **Categorical vs. Categorical** -- * When plotting the relationship between two categorical variables, stacked, grouped, or segmented bar charts are typically used -- * **Stacked bar chart** -- + Let’s plot the relationship between automobile class and drive type (front-wheel, rear-wheel, or 4-wheel drive) for the automobiles in the Fuel economy dataset. --- -- <!-- --> -- + From the chart, we can see for example, that the most common vehicle is the SUV. All 2seater cars are rear wheel drive, while most, but not all SUVs are 4-wheel drive. --- * **Grouped bar chart** -- + Grouped bar charts place bars for the second categorical variable side-by-side -- -- <!-- --> -- + Notice that all Minivans are front-wheel drive. By default, zero count bars are dropped and the remaining bars are made wider. This may not be the behavior you want. --- -- + You can modify; -- -- <!-- --> --- * **Segmented bar chart** -- + A segmented bar plot is a stacked bar plot where each bar represents 100 percent. -- -- <!-- --> -- + This type of plot is particularly useful if the goal is to compare the percentage of a category in one variable across each level of another variable. + For example, the proportion of front-wheel drive cars go up as you move from compact, to midsize, to minivan. --- -- * Can improve the segmented bar chart <!-- --> --- --- * Better still... -- <!-- --> --- * **Quantitative vs. Quantitative** -- + The relationship between two quantitative variables is typically displayed using; 1. scatterplots and 2. line graphs. -- * **Scatterplot** -- + The simplest display of two quantitative variables is a scatterplot, with each variable represented on an axis. -- -- + For example, using the Salaries dataset, we can plot experience (yrs.since.phd) vs. academic salary (salary) for college professors. -- -- <!-- --> --- * Enhanced -- <!-- --> -- * Clearly, salary increases with experience. However, there seems to be a dip at the right end - professors with significant experience, earning lower salaries. -- -- * A straight line does not capture this non-linear effect. A line with a bend will fit better here. --- -- * A polynomial regression line provides a fit line of the form ^y=β0+β1x+β2x2+β3x3+β4x4+… * Typically either a quadratic (one bend), or cubic (two bends) line is used. It is rarely necessary to use a higher order( >3 ) polynomials. Applying a quadratic fit to the salary dataset produces the following result. -- -- <!-- --> --- * **Line plot** -- + When one of the two variables represents time, a line plot can be an effective method of displaying relationship. -- -- + For example, the code below displays the relationship between time (year) and life expectancy (lifeExp) in the United States between 1952 and 2007. The data comes from the gapminder dataset. -- -- <!-- --> -- + It is hard to read individual values in the graph above. In the next plot, we’ll add points as well. --- -- <!-- --> --- # Categorical vs. Quantitative -- + When plotting the relationship between a categorical variable and a quantitative variable, a large number of graph types are available. + These include: 1. bar charts using summary statistics, 2. grouped kernel density plots, 3. side-by-side box plots, 4. side-by-side violin plots, 5. mean/sem plots, 6. ridgeline plots, and 7. Cleveland plots. --- # Bar chart (on summary statistics) -- + In previous sections, bar charts were used to display the number of cases by category for a single variable or for two variables. -- + You can also use bar charts to display other summary statistics (e.g., means or medians) on a quantitative variable for each level of a categorical variable. -- -- + For example, the following graph displays the mean salary for a sample of university professors by their academic rank. -- -- <!-- --> --- * We can make it more attractive with some options. -- <!-- --> + One limitation of such plots is that they do not display the distribution of the data - only the summary statistic for each group. The plots below correct this limitation to some extent. --- * **Grouped kernel density plots** -- * One can compare groups on a numeric variable by superimposing kernel density plots in a single graph. -- -- <!-- --> + The graph makes clear that, in general, salary goes up with rank. However, the salary range for full professors is very wide. --- # Box plots -- + A boxplot displays the 25th percentile, median, and 75th percentile of a distribution. The whiskers (vertical lines) capture roughly 99% of a normal distribution, and observations outside this range are plotted as points representing outliers (see the figure below). -- --- {width=10% height=15%} --- * Side-by-side box plots are very useful for comparing groups (i.e., the levels of a categorical variable) on a numerical variable. -- <!-- --> + Although not a formal test, if the notches of two boxplots do not overlap, there is strong evidence (95% confidence) that the medians of the two groups differ. --- # Violin plots -- + Violin plots are similar to kernel density plots, but are mirrored and rotated 90 degrees. -- <!-- --> --- # Multivariate Graphs -- + Multivariate graphs display the relationships among three or more variables. There are two common methods for accommodating multiple variables: 1. grouping and 2. faceting. -- -- <!-- --> --- * Next, let’s include the rank (third variable/dimension) of the professor, using color. -- <!-- --> --- * Finally, let’s add the gender of professor, using the shape of the points to indicate sex. -- <!-- --> * It is very busy, and it can be difficult to distinguish male from female professors. Faceting (described in the next section) would probably be a better approach. --- # Faceting -- + Grouping allows you to plot multiple variables in a single graph, using visual characteristics such as color, shape, and size. + In faceting, a graph consists of several separate plots or small multiples, one for each level of a third variable, or combination of variables. It is easiest to understand this with an example. -- -- <!-- --> --- -- * Salary historgrams by rank and gender -- <!-- --> --- * We can also combine grouping and faceting. * Let’s use Mean/SE plots and faceting to compare the salaries of male and female professors, within rank and discipline. * We’ll use color to distinguish sex and faceting to create plots for rank by discipline combinations. -- <!-- --> --- * As a final example, we’ll shift to a new dataset and plot the change in life expectancy over time for countries in the “Americas”. The data comes from the gapminder dataset in the gapminder package. Each country appears in its own facet -- <!-- --> * We can see that life expectancy is increasing in each country, but that Haiti is lagging behind. ---