L'objectif de cette fiche est de présenter les méthodes principales de génération de nombres pseudo-aléatoires, de comprendre leurs limitations, d'apprendre à s'en méfier et de voir comment éventuellement les corriger…

congruent_random <- function(n = 100, a = 4, b = 2, m = 9, x1 = 1) {

res = c(x1)

for (i in 2:n) {

res[i] = (a * res[i - 1] + b)%%m

}

res

}

Let's check whether this seems correct or not:

congruent_random(10)

## [1] 1 6 8 7 3 5 4 0 2 1

Now, let's make a few simple graphical checks

graphical_check <- function(X) {

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

hist(X)

plot(X[1:length(X) - 1], X[2:length(X)])

}

graphical_check(congruent_random(100))

Here is the ggplot2 version, just in case:

library(ggplot2)

require(gridExtra)

## Loading required package: gridExtra

## Loading required package: grid

graphical_check_ggplot <- function(X) {

par(mfrow = c(1, 2))

df <- data.frame(x = X[1:length(X) - 1], y = X[2:length(X)])

p1 <- ggplot(df, aes(x = x)) + geom_histogram() + theme_bw()

p2 <- ggplot(df, aes(x = x, y = y)) + geom_point() + theme_bw()

grid.arrange(p1, p2, ncol = 2)

}

graphical_check_ggplot(congruent_random(100))

## stat_bin: binwidth defaulted to range/30. Use 'binwidth = x' to adjust this.

OK, obviously, one cannot expect much from a generator whose space state is so small. Let's try with another one:

graphical_check_ggplot(congruent_random(n = 100, a = 11, b = 1, m = 71))

## stat_bin: binwidth defaulted to range/30. Use 'binwidth = x' to adjust this.

Yet, it you ever computed the correlation of {xn} and {x{n+1}} , you could have oversee this relation:

X <- congruent_random(n = 1000, a = 11, b = 1, m = 71)

cor(X[1:length(X) - 1], X[2:length(X)])

## [1] 0.04578

Co-variance would have helped though.

cov(X[1:length(X) - 1], X[2:length(X)])

## [1] 19.09

Fortunately, some generator are better than others:

graphical_check_ggplot(congruent_random(n = 1000, a = 24298, b = 99991, m = 199017))

## stat_bin: binwidth defaulted to range/30. Use 'binwidth = x' to adjust this.

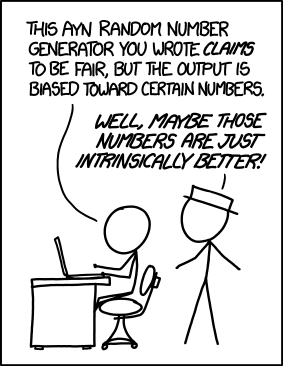

Anyway, you should always be suspicious with random number generators. After all, although the previous two graphical checks seem comforting, there are probably other biases left…

X = (xor_random <- function(n = 100, filter = c(1, 0, 1, 0), seed = c(1, 0,

1, 0)) {

res = seed

m = length(filter)

print(m)

for (i in (length(seed)):(n - 1)) {

# Yes, you need to put parenthesis around n-1 :(

res[i + 1] = sum(filter * (res[(i - m + 1):i]))%%2 # Yes, you need to put parenthesis around i-m+1 :(

}

res

})

xor_random()

## [1] 4

## [1] 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0

## [36] 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0

## [71] 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0 0 0 1 0 1 0

xor_random(seed = c(1, 0, 0, 1))

## [1] 4

## [1] 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1

## [36] 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1

## [71] 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 1

Yuck. This is definitely not random… Actually, there are two interleaved sequences. The length of the cycle is 8. Let's try something different.

xor_random(filter = c(1, 1, 0, 0), seed = c(1, 1, 0, 1))

## [1] 4

## [1] 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0

## [36] 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0

## [71] 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0 0 0 1 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 1 1 1 1 0

That's better. Now the length of the cycle is 16.