Influenza and Pneumonia Mortality during the Global COVID-19 Pandemic and the Impact of Local Government Restrictions

Angel Claudio, Bonnie Cooper, Manolis Manoli, Magnus Skonberg, Christian Thieme, Leo Yi

"2021-05-23"

Communicable Disease during COVID-19

The global COVID-19 pandemic has greatly impacted disease beyond direct cases of COVID-19.

Reports have identified statistically significant decreases in diagnoses for communicable diseases such as pneumonia and influenza.\( ^{1,2,3} \)

Hypothesis 1: Disease mitigation efforts (e.g. masks, social distancing) have directly reduced non-COVID disease cases.

Other reports show that while disease diagnostic rates have decreased for diseases such as heart attack and stroke, mortality rates for these diseases have increased during COVID.\( ^{4,5,6} \)

Hypothesis 2: Changes in patient behavior and health care availability during the pandemic have led to missed cases of disease.

Our Goal: Use U.S. state-level disease data on pneumonia and influenza in conjunction with data on state government enforced COVID regulations to look for an association between disease and disease mitigation efforts.

If government restriction data significantly impacts the modeling of pneumonia and influenza mortality data, we interpret this as support for Hypothesis 1

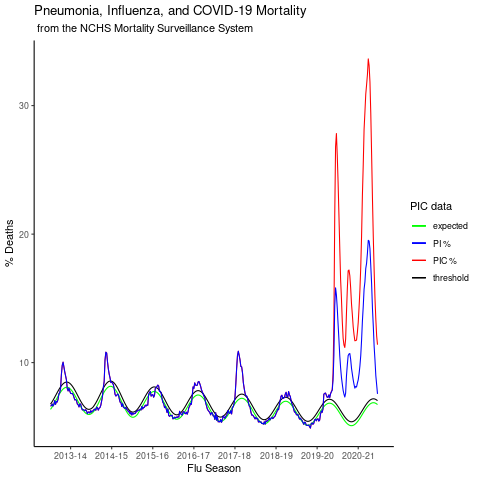

Pneumonia, Influenza and COVID-19 mortality in the U.S.

- If PI deaths decreased during COVID, PI mortality should be below the expected rate.

- However, here we observe that PI deaths during COVID are in excess and follow the trend of COVID data

- Next, we quantify the excess PI deaths at the state-level

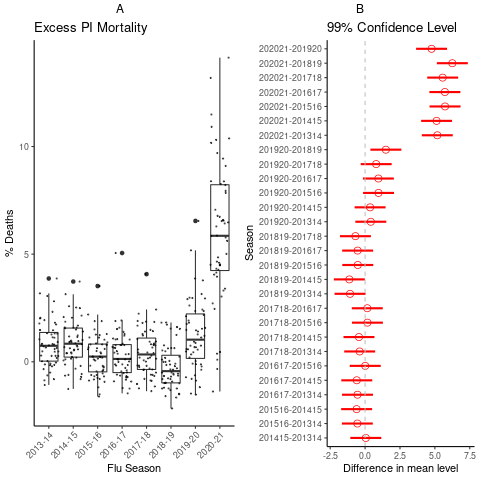

State-level excess Pneumonia and Influenza mortality

We measured the excess PI mortality as:

\[ \mbox{Excess PI} = \\ \mbox{max}( \mbox{PI}_{weekly} - \mbox{expected}_{weekly}) \]

Excess PI for the 2020-21 flu season is significantly different when compared to all other flu seasons in our dataset

Next, we look at the relationship of excess PI deaths and COVID related deaths

Figure A) state-level excess PI

Figure B) Tukey Honest Significant Differences of Means test

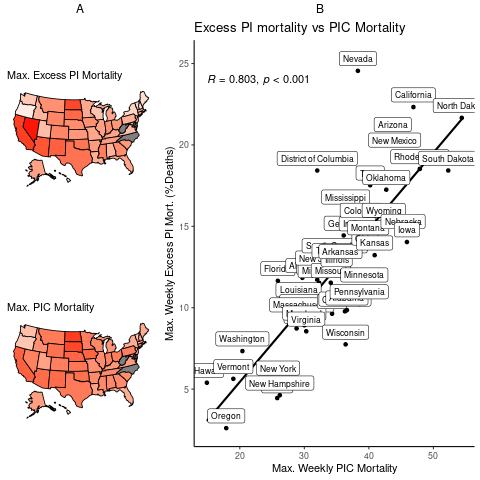

State-level relationship of excess PI mortality and PIC mortality

We observe a strong correlation between excess PI deaths and COVID related deaths

- States high in excess PI mortality are associated with high COVID-related deaths

- A) State-level heat map for excess PI (top) and COVID related mortality (bottom)

- B) Strong linear relationship between excess PI and COVID related deaths

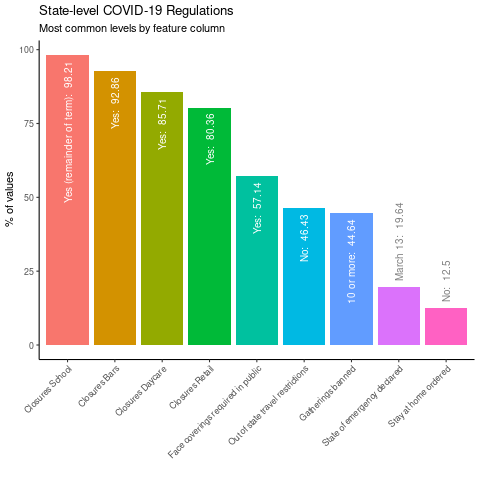

State-level Government COVID-19 Restriction Data

To test Hypothesis 1 we incorporated state-level government restriction data

- This figure shows the most common levels of each government restriction categorical feature variable

- We also added state-level demographic features such a population and population density

Modeling Excess PI Mortality with Government Restriction Data

To model the impact of government restriction data on excess PI mortality, we used a simple linear regression model as a baseline (Model 1) and developed four additional models:

- Model 2 - AIC step-wise multiple regression engineered binary variables to recode and simplify government restriction data.

- Model 3 - AIC step-wise multiple regression of categorical government restriction data + state-level demographic features

- Model 4 - Ridge-regression feature selection using Model 3 feature set

- Model 5 - Lasso-regression feature selection using Model 3 feature set

Model Comparison Table

| Model | Method | Var_Num | R2_train | RMSE_train | R2_test | RMSE_test |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Simple Linear | 1 | 0.8056 | 2.3288 | 0.8056 | 2.5144 |

| 2 | Mult. Linear | 7 | 0.8207 | 2.2255 | 0.8207 | 2.3869 |

| 3 | Mult. Linear | 8 | 0.8434 | 2.0714 | 0.8434 | 2.3098 |

| 4 | Ridge | 6 | 0.8403 | 2.1129 | 0.7875 | 2.3333 |

| 5 | Lasso | 6 | 0.8403 | 2.1129 | 0.7874 | 2.3341 |

Table 1: Model performance metrics used to evaluate and select from different modeling approaches

Model Selection

- Model 3, the AIC step-wise multiple regression model, was selected due to it's parsimonious explanation of the data's variance balanced with fewer number of predictor variables.

- Model 3 has a highly significant fit (p-val < 2.2e-16) and a high \( R^2 \) values

- Model 3 results in a significantly lower residual sum of squares compared to the simple linear model (Model 1)

- Conclusion including government restriction data resulted in a better description of excess PI mortality data

Model Evaluation

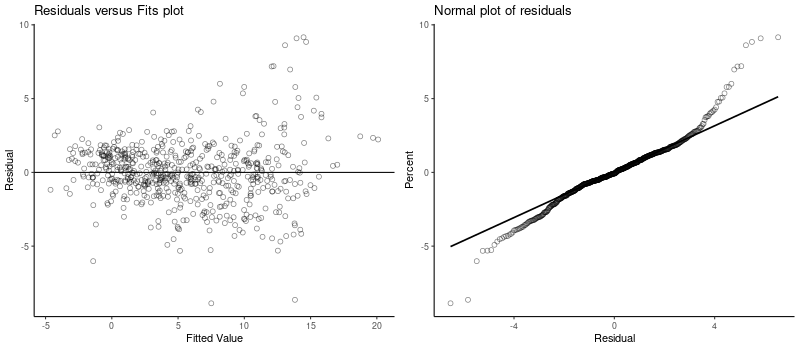

Although our model improves upon the description of excess PI mortality, there is room for improvement: diagnostic plots reveal that residual variance is not constant across the model fit (left panel) and the normality plot of residuals suggests high-skewed distribution

Summary & Conclusions

- On a national level, U.S. PI deaths were significantly higher during the COVID-19 global pandemic. However, interpretation of this finding is complicated by the fact that pneumonia, influenza and COVID-19 cases and deaths data are confounded.\( ^{7,8} \)

- Incorporating state-level government regulation data resulted in a better description of excess PI mortality during the 2020-21 flu season. This supports Hypothesis 1

- Model 3 is a first step towards modeling the impact of government regulations on communicable diseases during COVID. However, there is much room for improvement and many avenues for future research:

- adding more features: government restriction &/or demographic variables

- extending the analysis to data from other countries or larger geographic scales

- focusing the analysis to data on a county/province/community scale

- performing the same analysis after more time has been allowed to complete mortality records

References

- Olsen SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Budd AP, et al. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic—United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. American Journal of Transplantation 2020; 20(12): 3681–3685.

- Angoulvant F, Ouldali N, Yang DD, et al. COVID-19 pandemic: impact caused by school closure and national lockdown on pediatric visits and admissions for viral and non-viral infections, a time series analysis. Clinical Infectious Diseases 2020.

- Chiu NC, Chi H, Tai YL, et al. Impact of wearing masks, hand hygiene, and social distancing on influenza, enterovirus, and all-cause pneumonia during the coronavirus pandemic: Retrospective national epidemiological surveillance study. Journal of Medical Internet Research 2020; 22(8): e21257.

- Baldi E, Sechi GM, Mare C, et al. COVID-19 kills at home: the close relationship between the epidemic and the increase of out-of-hospital cardiac arrests. European heart journal 2020; 41(32): 3045–3054.

- Wadhera RK, Shen C, Gondi S, Chen S, Kazi DS, Yeh RW. Cardiovascular deaths during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2021; 77(2): 159–169.

- Sharma R, Kuohn LR, Weinberger DM, et al. Excess Cerebrovascular Mortality in the United States During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Stroke 2020: STROKEAHA–120.

- Beusekom MV. About 30% of COVID deaths may not be classified as such. 2020.

- Faust JS, Del Rio C. Assessment of deaths from COVID-19 and from seasonal influenza. JAMA internal medicine 2020; 180(8): 1045–1046.