ENG330 - Hydrology for Engineers ebook

Dr Helen Fairweather, University of the Sunshine Coast

30 August, 2019

- 1 Preamble

- 2 Referencing Your Work in Knitr

- 3 Getting started with R

- 4 An introduction to using R

- 5 Beyond the R basics

- 6 Matrix arithmetic in R

- 7 Where to now?

- 8 Tutorial 1 - Hydrologic Data in R

- 9 Theme 1 Module 1: The hydrologic cycle

- 10 Tutorial 2: Creating a water balance

- 11 Theme 1, Topic 3: Statistics for Hydrology

- 12 Topic 4: Flood Frequency Analysis

- 13 Tutorial 4: Flow Duration Curves

- 14 Theme 2, Topic 1: RAINFALL and IFD data

- 15 Tutorial 5: IFD curves in R

- 16 Topic 1 - Flood Hydrographs

- 17 Topic 2 - Flood Routing Concepts and Models

- 18 Tutorial 6: Runoff routing

- 19 Tutorial 7: Find the area, mainstream length and equal area slope of the Coochin Creek catchment.

- 20 References

1 Preamble

This document was developed as part of a Learning and Teaching project, funded by the University of the Sunshine Coast. The project’s formal title is “Develop your own Lifelong Learning Resource: Learners as Active Collaborators”, but the shortened title is “Write your own…”

The R programming language is being used to develop this resource enabling students to build an e-portfolio of text with the R code required to run the various hydrological methods embedded within the resource. Using the Knitr library, students are able to re-run the code for different datasets and locations and update methods as they change. The intent is to develop a life-long learning resource that can be developed for any subject or endeavour.

Throughout the course students are provided with a series of templates with the .Rmd extension. These are knitted together by this Master Document. In any of the templates, wherever a directory appears, you will need to point to the relevant directory on your computer.

To create the linked Table of Contents in the left-hand frame you will need to follow these instructions. Each module is embedded into this main document by adding a ‘chunk’ and include in the r argument list: child=“module1.Rmd”, replacing the module1 with the appropriate file name.

2 Referencing Your Work in Knitr

Referencing (or citations) in Knitr are surprisingly easy using the knitcitations package, once you have figured out how to do it! The learning path is steep, so I am providing you with some tips, so that hopefully it will work for you first time. However, this may not be the best way to do it, so if you do come up with a better method, can you please let myself and everyone else know on the discussion board.

Most modern references include a DOI (or Digital Object Identifier), which makes it very easy to reference documents in your .Rmd file.

To install the knitcitations module you need to implement the following code:

library(devtools)

install_github("knitcitations", "cboettig")library("knitcitations")

library("RefManageR")

cleanbib()

#You need to put your directory into the following code (shown in red):

bib <- read.bibtex("~/OneDrive - University of the Sunshine Coast/Courses/ENG330/ENG330_ebook/references.bib")For example, a relevant paper on IFD Temporal Patterns is from French and Jones (2012), and this reference is created using the citet (or citep) functions. Experiment with the use of these two functions (one puts the whole reference in parenthesis and the other just the year).

There are of course files that you will need to reference that do not have a DOI, and in this case you will need to input the relevant fields into a ‘.bib’ file. The format for inputting these ‘old’ references is surprisingly simple. For example, the Hill and Mein (1996) is a reference, the details for which I have copied from the article itself (see below). These details can be entered into a text file within the RStudio environment.

After the identifier @article, the first entry is a ‘key’ to make it easier to reference. The code to enter the Hill and Mein (1996) reference is “r citet(bib[[“Hill1996”]])”, (or citep, depending on how you want the parenthesis configured), where “Hill1996”" is the ‘key’.

@article{Hill1996,

abstract = {Anomalies in design flood estimates can arise from the design temporal patterns and losses. This study shows the effect that intense bursts within longer duration design storms can have on flood estimates, and recommends filtering of the temporal patterns. It also presents the results of a pilot study in which losses are derived to be consistent with the nature of design rainfalls; the result was a significant improvement in design flood accuracy.},

author = {Hill, P. J. and Mein, R. G.},

journal = {23rd Hydrology and Water Resources Symposium Hobart Australia 21-24 May 1996},

month = may,

number = {5},

pages = {445--51},

title = {{Incompatibilities between Storm Temporal Patterns and Losses for Design Flood Estimation.}},

year = {1996}

}To generate a bibliography the following code is entered (with echo=FALSE included if you do not want the code block to print).

You should also reference the packages you have used in producing your document, as well as RStudio itself. Fortunately Boettiger (2017) has made this possible also. Your bibliography will also include these citations.

This page was created in Rstudio: #r citet(citation("rstudio")) , with the packages knitr: Xie (2019); Xie (2015); Xie (2014), knitcitations: Boettiger (2017), and RefManageR: McLean (2017); McLean (2014).

bibliography()[1] C. Boettiger. knitcitations: Citations for ‘Knitr’ Markdown Files. R package version 1.0.8. 2017. <URL: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=knitcitations>.

FALSE No encoding supplied: defaulting to UTF-8.[1] P. J. Hill and R. G. Mein. “Incompatibilities between Storm Temporal Patterns and Losses for Design Flood Estimation.”. In: 23rd Hydrology and Water Resources Symposium Hobart Australia 21-24 May 1996 (May. 1996), pp. 445-51.

FALSE No encoding supplied: defaulting to UTF-8.[1] M. W. McLean. Straightforward Bibliography Management in R Using the RefManager Package. arXiv: 1403.2036 [cs.DL]. 2014. <URL: https://arxiv.org/abs/1403.2036>. [1] Y. Xie. Dynamic Documents with R and knitr. 2nd. ISBN 978-1498716963. Boca Raton, Florida: Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2015. <URL: https://yihui.name/knitr/>. [1] Y. Xie. “knitr: A Comprehensive Tool for Reproducible Research in R”. In: Implementing Reproducible Computational Research. Ed. by V. Stodden, F. Leisch and R. D. Peng. ISBN 978-1466561595. Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2014. <URL: http://www.crcpress.com/product/isbn/9781466561595>. [1] Y. Xie. knitr: A General-Purpose Package for Dynamic Report Generation in R. R package version 1.23. 2019. <URL: https://yihui.name/knitr/>.

3 Getting started with R

3.1 About R

R is a powerful and convenient environment for analysis of data, especially statistical analysis of data.

R is not a menu-driven statistical package, but uses a command line.

R is a powerful environment for statistically and graphically analyzing data.

3.2 Getting and installing R

R can be downloaded from http://cran.r-project.org/mirrors.html (the Comprehensive R Archive Network, or CRAN). First select an Australian mirror from this link, then click on ‘Download and Install R’, then download the pre-compiled binaries for your operating system. Then install these pre-compiled binaries in the usual way for your operating system.

Another useful website is http://www.r-project.org/ (the R Homepage).

4 An introduction to using R

4.1 Basic use of R as a calculator

After starting R, a command line is presented indicating that R is waiting for the user to enter commands. This command line usually looks like this:

>Instruct R to perform basic arithmetic by issuing commands at the command line, and pressing the Enter or Return key. To try it out, start R, enter the following command and then press Enter:

9 * (1 - 3) + (8/4)## [1] -16Note that * indicates multiplication, and / indicates division.

After giving the answer, R then awaits your next instruction. Note that the answer here is preceded by [1], which indicates the first item of output, and is of little use here where the output consists of one number. But sometimes R produces many numbers as output, when the [1] proves useful. Other examples of the basic use of R:

2 * pi # pi means 3.14159265...## [1] 6.283185-8 + ( 2^3 ) # ^ means to raise to the power## [1] 010/4000000 # The answer is in scientific notation## [1] 2.5e-06Note the use of #: the # character is a comment character, so that # and all text after it is ignored by R. The output from the final expression 2.5e-06 is R’s way of displaying \(2.5\times 10^{-6}\). Very large or very small numbers can be entered using this notation also:

6.02e23 # Avogadro constant## [1] 6.02e+23Standard mathematical functions are also defined in R:

log( 10 ) # Notice that log is the natural log to base e = 2.71828...## [1] 2.302585log10(10) #This is log to base 10## [1] 1sin( pi ) # The result is zero to computer precision ## [1] 1.224647e-16sqrt( 45 ) # The square root## [1] 6.708204Issuing incomplete R commands forces R to wait for the command to be completed. So, for example, if you type:

cos( 2*and press Enter, R will wait for you to finish the command. The command prompt then changes to a plus sign:

+4.2 Quitting R

To finish using R, enter

q()at the command prompt (and yes, the brackets are necessary). R usually asks you if you wish to save your workspace; that is, whether or not you want R to save all your data and variables that you have defined. Unless you really need this, say No, because you can quickly end up with far too many variables saved.

4.3 Variable names in R

Importantly, answers computed by R can be assigned to variables using the two-character combination <-:

radius <- 0.605

area <- pi * radius^2

area## [1] 1.149901Notice that when <- is used, the answer is not displayed unless the name of a variable is entered as its own command. The equal sign = can be used in place of <- to make assignments but is not as commonly used:

radius = 0.605In fact, not only can you use <- but you can also use ->:

2 -> x; x## [1] 2You can even use <- and -> together:

y <- 4 -> z

y; z## [1] 4## [1] 4As shown, commands can be issued together on one line if separated by a ; (a semi-colon).

You do need to be careful when you use <- however. For example, what does this mean: x<-4? It could mean to assign x the value of 4:

x <- 4

x## [1] 4Or it could mean a logical comparison, asking if the value of x is less than -4:

x < (-4)## [1] FALSEBecause of this, using spaces wisely is important. Spaces in the input are not important to R. All these commands mean the same to R, but the first is easiest to read, so is preferred:

area <- pi * radius^2

area <- pi *radius^ 2

area<-pi*radius^2Variable names can consist of letters, digits, the underscore character, and the dot (period). Variable names cannot start with digits; names starting with dots should be avoided. Variable names are also case sensitive: HT, Ht and ht are different variables to R. Many possible variables names are already in use (reserved) by R, such as log as used above. Problems may result if these are used as variable names. Common variables names to avoid include:

t(used for transposing matrices),c(used for combining objects),q(used for quitting R),T(is a logical true, though usingTRUEis preferred),F(is a logical false, though usingFALSEis preferred), anddata(used to make data sets available to R).

These are all valid variables names:

plant.heightPatientAgeInitial_Dosedose2circuit.2.AM

These are not valid variables names:

Before-After(the-is illegal)2ndTrial(starts with a digit)

4.4 Working with vectors

R works especially well with a group of numbers, called a vector. Vectors are created by grouping items together using the function c() (for ‘combine’ or ‘concatenate’):

x <- c(1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10)

log(x)## [1] 0.0000000 0.6931472 1.0986123 1.3862944 1.6094379 1.7917595 1.9459101

## [8] 2.0794415 2.1972246 2.3025851A long sequence of equally-spaced values is often useful, especially in plotting. Rather than the cumbersome approach adopted above, consider these simpler approaches:

seq(0, 10, by=1) # The values are separated by distance 1## [1] 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 100:10 # Same as above## [1] 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10seq(0, 10, length=29) # The result has length 29## [1] 0.0000000 0.3571429 0.7142857 1.0714286 1.4285714 1.7857143

## [7] 2.1428571 2.5000000 2.8571429 3.2142857 3.5714286 3.9285714

## [13] 4.2857143 4.6428571 5.0000000 5.3571429 5.7142857 6.0714286

## [19] 6.4285714 6.7857143 7.1428571 7.5000000 7.8571429 8.2142857

## [25] 8.5714286 8.9285714 9.2857143 9.6428571 10.0000000Notice that the output is long, so R identifies which element numbers starts each row of output.

Variables do not have to be numerical; text and logical variables can also be used:

day <- c("Sun", "Mon", "Tues", "Wed", "Thurs", "Fri", "Sat")

hours.work <- c(0, 8, 11.5, 9.5, 8, 8, 3)

hours.sleep <- c(8, 8, 9, 8.5, 6, 7, 8)

do.exercise <- c(TRUE, TRUE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE, FALSE, TRUE)

hours.play <- 24 - hours.work - hours.sleep

hours.awake <- hours.work + hours.playSingle or double quotes are possible for defining text variables, though double quotes are preferred (which enables constructs like "O’Neil"). Specific elements of a vector are identified using square brackets:

hours.play[3]; hours.work[ 7 ]## [1] 3.5## [1] 3To find the value of hours.work on Fridays, consider the following:

day=="Fri" # A logic statement: == compares two objects to see if they are equal## [1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSEhours.work[ day=="Fri" ]## [1] 8hours.sleep[ day=="Fri" ]## [1] 7do.exercise[ day=="Thurs"]## [1] TRUENotice that == is used for logical comparisons. Other logical comparisons are also possible:

day[ hours.work > 8 ] # > means "greater than"## [1] "Tues" "Wed"day[ hours.sleep < 8 ] # < means "less than"## [1] "Thurs" "Fri"day[ hours.work >= 8 ] # >= means "greater than or equal to"## [1] "Mon" "Tues" "Wed" "Thurs" "Fri"day[ hours.work <= 8 ] # <= means "less than or equal to"## [1] "Sun" "Mon" "Thurs" "Fri" "Sat"day[ hours.work != 8 ] # != means "not equal"## [1] "Sun" "Tues" "Wed" "Sat"day[ do.exercise & hours.work>8 ] # & means "and"## [1] "Tues"day[ hours.play>9 | hours.sleep>9 ] # | means "or"## [1] "Sun" "Thurs" "Sat"5 Beyond the R basics

5.1 Using functions in R

Working with R requires using R functions. R contains a large number of functions, and the many additional packages add even more functions as needed. Many R functions have been used already, such as q(), seq() and log(). Input arguments to R functions are enclosed in round brackets (parentheses), as previously seen. All R functions must be followed by parentheses, even if they are empty. (For example, recall the function q() for quitting R.)

Many functions allow several input arguments. Inputs to R functions can be specified as positional or named, or even both in the one call. Positional specification means the function reads the inputs in the order in which function is defined to read them. For example, the R help for the function log() contains this information in the Usage section:

log(x, base = exp(1))The help file indicates that the first argument is always the number for which the logarithm is needed, and the second (if provided) is the base for the logarithm. Previously, log() was called with only one input, not two. If input arguments are not given, defaults are used when available. The above extract from the help file shows that the default base for the logarithm is \(e\approx2.71828\dots\) (that is, exp(1)) if the user does not specify any base explicitly. In contrast, there is no default value for x. This means that if log() is called with only one input argument, the result is a natural logarithm (since base=exp(1) is used by default). To specify a logarithm to a different base, say base 2, a second input argument is needed:

log(8, 2) # The log of 8 to base 2; the same as log2(8)This is an example of specifying the inputs by position. Alternatively, all or some of the arguments can be named. For example, all these commands are identical:

log(x=8, base=2)## [1] 3log(8, 2)## [1] 3log(base=2, x=8) # If the order is different than the function definition, inputs must be named## [1] 3log(8, base=2)## [1] 35.2 Using R Packages

R comes with many extra packages that extend the capabilities of R. If you go to one of the CRAN sites and select Packages, you will find a very long list of R packages that you can install. A very long list…

Some packages (such as MASS) come with R. Some packages must first be downloaded and installed:

- Installing: If you need to download and install an R package, go to CRAN and select the package to download.

- Sometimes you can use the R function

install.packages(). Sometimes, however, that doesn’t work.

To then use an R package, that package must be loaded before being used in any R session:

Loading: To load an installed package and so make the extra functionality available to R, type (for example)

library(MASS)at the R prompt.

(Note that packageMASScomes with R, and you do not have to first download it.)Using: After loading the package, the functions in the package can be used like any other function in R.

Obtaining help: To obtain help about a loaded package, type

library(help=MASS)at the R prompt. To obtain help about any particular function or dataset in the package, type (for example)?logat the R prompt after the package is loaded.

5.3 Loading data into R

In statistics, data are usually stored in computer files, which must be loaded into R. R requires data files to be arranged with variables in columns, and cases in rows. Columns may have headers containing variable names; rows may have headers containing case labels. In R, data are usually treated as a data frame, a set of variables (numeric, text, logical, or other types) grouped together. For the data entered in before, a single data frame named my.week could be constructed:

my.week <- data.frame(day, hours.work, hours.sleep,

do.exercise, hours.play, hours.awake)

my.week## day hours.work hours.sleep do.exercise hours.play hours.awake

## 1 Sun 0.0 8.0 TRUE 16.0 16.0

## 2 Mon 8.0 8.0 TRUE 8.0 16.0

## 3 Tues 11.5 9.0 TRUE 3.5 15.0

## 4 Wed 9.5 8.5 FALSE 6.0 15.5

## 5 Thurs 8.0 6.0 TRUE 10.0 18.0

## 6 Fri 8.0 7.0 FALSE 9.0 17.0

## 7 Sat 3.0 8.0 TRUE 13.0 16.0Entering data directly into R is only feasible for small amounts of data Usually, other methods are used for loading data into R:

- If the dataset comes with R, load the data using the command

data(trees)(for example). This command loads thetreesdataset which comes with R. Typedata()at the R prompt to see a list of all the example data that comes with R. - If the data are in an installed R package, load the package, then use

data()to load the data. - If the data are stored as a text file (either on a disk or on the internet), R provides a set of functions for loading the data:

read.csv(): Reads comma-separated text files. In files where the comma is a decimal point and fields are separated by a semicolon, useread.csv2().read.delim(): Reads delimited text files, where fields are delimited by tabs by default. In files where the comma is a decimal point, useread.delim2().read.table(): Reads files where the data in each line is separated by one or more spaces, tabs, newlines or carriage returns.read.table()has numerous options for reading delimited files.read.fwf(): Reads data from files where the data are in a fixed width format (that is, the data are in fields of known widths in each line of the data file). Use these functions by typing, for example,mydata <- read.csv("filename.csv")

- For data stored in file formats from other software (such as SPSS, Stata, and so on), first load the package

foreign, then seelibrary(help=foreign). Not all functions in the foreign package load the data as data frames by default (such asread.spss()).

Many other inputs are also available for these functions (see the relevant help files). All these functions load the data into R as a data frame. These functions can be used to load data directly from a web page (providing you are connected to the internet) by providing the URL as the filename. For example, the data set twomodes.txt is available in tab-delimited format at the OzDASL webpage (http://www.statsci.org/data), with variable names in the first row (called a header):

modes <- read.delim("http://www.statsci.org/data/general/twomodes.txt",

header=TRUE)5.4 Working with data frames

Data loaded from files (using read.csv() and similar functions) or using the data() command are loaded as a data frame. A data frame is a set of variables (numeric, text, or other types) grouped together, as previously explained. For example, the data frame cars comes with R. The help for the file can be read by typing

help(cars)or, more succinctly:

?carsThe data frame contains two variables: speed and dist, which can be seen from the names() command:

names(cars)## [1] "speed" "dist"Alternatively, you can look at the top of the data file as follows:

head(cars)## speed dist

## 1 4 2

## 2 4 10

## 3 7 4

## 4 7 22

## 5 8 16

## 6 9 10The data frame cars is visible to R, but the individual variables within this data frame are not visible; this code:

speedwill fail because R can see the cars data frame but not what variables are within this data frame. The objects that are visible to R are displayed using objects():

objects()## [1] "Apr" "area" "Aug" "bib"

## [5] "bits" "bmins" "brain" "c"

## [9] "ci" "cn" "cnames" "colvec"

## [13] "date_fin" "date_ind" "date_st" "datech"

## [17] "day" "dd" "ddtemp" "Dec"

## [21] "direc" "dirv" "do.exercise" "dt"

## [25] "dt_eventends" "dt_max_dur" "dur_hrs" "Feb"

## [29] "findate" "findt" "fn" "fname"

## [33] "hd" "hours.awake" "hours.play" "hours.sleep"

## [37] "hours.work" "i" "i930" "ifd"

## [41] "ifdl" "ifdp" "indevent" "iv"

## [45] "Jan" "Jul" "Jun" "labvec"

## [49] "M" "Mar" "max_dur" "May"

## [53] "mfd" "monv" "my.week" "ncol"

## [57] "Nov" "nv" "Oct" "radius"

## [61] "rrain" "rrv" "rrv_temp" "Sep"

## [65] "seq_v" "stdate" "stday" "stdt"

## [69] "sthr" "stmin" "stn" "sumv"

## [73] "timech" "timv" "tseq" "tt"

## [77] "varn" "x" "xlab" "y"

## [81] "ylab" "yv" "z" "zd"

## [85] "zdd" "zrain" "zz"To refer to individual variables in the data frame cars, use $ between the data frame name and the variable name, as follows:

cars$speed## [1] 4 4 7 7 8 9 10 10 10 11 11 12 12 12 12 13 13 13 13 14 14 14 14

## [24] 15 15 15 16 16 17 17 17 18 18 18 18 19 19 19 20 20 20 20 20 22 23 24

## [47] 24 24 24 25This construct can become tedious to use all the time. An alternative is to attach the data frame so that the individual variables are visible to R:

attach(cars); speed## [1] 4 4 7 7 8 9 10 10 10 11 11 12 12 12 12 13 13 13 13 14 14 14 14

## [24] 15 15 15 16 16 17 17 17 18 18 18 18 19 19 19 20 20 20 20 20 22 23 24

## [47] 24 24 24 25When finished using the data frame, detach it:

detach(cars)Another alternative is to use with(), by noting the data frame in which the command should executed:

with( cars, mean(speed))## [1] 15.45.5 Basic statistical functions

Basic statistical functions are part of R:

data(cars); attach(cars)

length( cars$speed ) # The number of observations## [1] 50sum(cars$speed) / length(cars$speed) # The mean, the long way## [1] 15.4mean( cars$speed) # The mean, the short way## [1] 15.4median( cars$speed ) # The median## [1] 15sd( cars$speed) # The standard deviation## [1] 5.287644A summary of the dataset can be found using summary():

summary(cars)## speed dist

## Min. : 4.0 Min. : 2.00

## 1st Qu.:12.0 1st Qu.: 26.00

## Median :15.0 Median : 36.00

## Mean :15.4 Mean : 42.98

## 3rd Qu.:19.0 3rd Qu.: 56.00

## Max. :25.0 Max. :120.005.6 Basic plotting in R

R has very rich and powerful mechanisms for producing graphics. Simple plots are easily produced, but very fine control over many graphical parameters is possible. Consider a simple plot for the cars data:

plot( cars$dist ~ cars$speed) # That is, plot( y ~ x)

The ~ command (~ is called a tilde) can be read as ‘is described by’. The variable on the left of the tilde appears on the vertical (or \(y\)) axis. An equivalent command to the above plot() is:

plot( dist ~ speed, data=cars )

Notice the axes are then labelled differently. As a general rule, R functions that use the formula interface (that is, constructs such as dist ~ speed) allow an input called data in which the data frame containing the variables is given. The plot() command can also be used without using a formula interface:

plot( speed, dist ) # That is, plot(x, y)

Using this approach, the variable appearing as the second input is plotted on the vertical axis.

These plots so far have all been simple, but R allows many details of the plot to be changed. Compare the result of the following code with the earlier code:

plot( dist ~ speed,

data = cars, # The data frame containing the variables

las=1, # Makes the axis labels all horizontal

pch=19, # Plots with a filled circle; see ?points

xlim=c(0, 25), # Set the x-axis limits to 0 and 25

xlab="Speed (in miles per hour)", # The label for the x-axis

ylab="Stopping distance (in feet)", # The label for the y-axis

main="Stopping distance vs speed for cars\n(from Ezekiel (1930))") # Main title

5.7 More advanced plotting

Plots can be enhanced in many ways, and many other types of plots exist. Consider this plot which examines 32 cars from 1974:

data(mtcars) # Load the data. Try ?mtcars for a description

summary(mtcars)## mpg cyl disp hp

## Min. :10.40 Min. :4.000 Min. : 71.1 Min. : 52.0

## 1st Qu.:15.43 1st Qu.:4.000 1st Qu.:120.8 1st Qu.: 96.5

## Median :19.20 Median :6.000 Median :196.3 Median :123.0

## Mean :20.09 Mean :6.188 Mean :230.7 Mean :146.7

## 3rd Qu.:22.80 3rd Qu.:8.000 3rd Qu.:326.0 3rd Qu.:180.0

## Max. :33.90 Max. :8.000 Max. :472.0 Max. :335.0

## drat wt qsec vs

## Min. :2.760 Min. :1.513 Min. :14.50 Min. :0.0000

## 1st Qu.:3.080 1st Qu.:2.581 1st Qu.:16.89 1st Qu.:0.0000

## Median :3.695 Median :3.325 Median :17.71 Median :0.0000

## Mean :3.597 Mean :3.217 Mean :17.85 Mean :0.4375

## 3rd Qu.:3.920 3rd Qu.:3.610 3rd Qu.:18.90 3rd Qu.:1.0000

## Max. :4.930 Max. :5.424 Max. :22.90 Max. :1.0000

## am gear carb

## Min. :0.0000 Min. :3.000 Min. :1.000

## 1st Qu.:0.0000 1st Qu.:3.000 1st Qu.:2.000

## Median :0.0000 Median :4.000 Median :2.000

## Mean :0.4062 Mean :3.688 Mean :2.812

## 3rd Qu.:1.0000 3rd Qu.:4.000 3rd Qu.:4.000

## Max. :1.0000 Max. :5.000 Max. :8.000plot( mpg ~wt,

data = mtcars,

las=1, # Makes the axis labels all horizontal

type="n", # This doesn't do any plotting, but sets up the axes

xlab="Weight (in thousands of pounds)", # The label for the x-axis

ylab="Fuel economy (in miles per gallon)", # The label for the y-axis

main="Fuel economy vs weight of car\nfor 32 cars in 1970") # The main plot title

points( mpg ~ wt, data=mtcars, pch=15,

subset=(cyl==4), col="green" ) # points() adds points to the current plot

points( mpg ~ wt, data=mtcars, pch=17,

subset=(cyl==6), col="orange" ) # See ?points for what these plotting characters

points( mpg ~ wt, data=mtcars, pch=19, # show. For example, 15 is a filled square

subset=(cyl==8), col="red" )

legend("topright", pch=c(15, 17, 19), col=c("green", "orange", "red"),

legend=c("4 cylinders", "6 cylinders", "8 cylinders")) # Adds a legend

Here are some different plots. First, a boxplot:

boxplot( mpg ~ cyl, data=mtcars,

xlab="Number of cylinders",

ylab="Fuel economy (in miles per gallon)",

las=1,

main="Fuel economy for 4, 6 and 8 cylinder cars",

col=c("green", "orange", "red"))

Now a barchart (in R this is called a barplot):

barplot( table(mtcars$cyl),

col="wheat",

las=1,

xlab="Number of cylinders",

ylab="Number of cars in the sample")

Here is an interesting one, adding a smoothing line to the plot:

scatter.smooth(mtcars$wt, mtcars$mpg, # Adds a `smooth' line

las=1, # Makes the axis lables all horizontal

type="n", # This doesn't do any plotting, but sets up the axes

xlab="Weight (in thousands of pounds)", # The label for the x-axis

ylab="Fuel economy (in miles per gallon)", # The label for the y-axis

main="Fuel economy vs weight of car\nfor 32 cars in 1970") # The main plot title

points( mpg ~ wt, data=mtcars, pch=15, subset=(cyl==4), col="green" )

points( mpg ~ wt, data=mtcars, pch=17, subset=(cyl==6), col="orange" )

points( mpg ~ wt, data=mtcars, pch=19, subset=(cyl==8), col="red" )

legend("topright", pch=c(15, 17, 19), col=c("green", "orange", "red"),

legend=c("4 cylinders", "6 cylinders", "8 cylinders"))

6 Matrix arithmetic in R

R performs matrix arithmetic using some special functions. A matrix is defined using matrix() where the matrix elements are given with the input data, the number of rows with nrow or columns with ncol (or both), and optionally whether to fill down columns (the default) or across rows (by setting byrow=TRUE):

Amat <- matrix( c(1, 2, -3, 4), ncol=2) # Fills by columns

Amat## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 -3

## [2,] 2 4Bmat <- matrix( c(1,2,-3, 10,-20,30), nrow=2, byrow=TRUE) # Fill by row

Bmat## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 1 2 -3

## [2,] 10 -20 30Standard matrix operations can be performed:

dim( Amat ) # The dimensions of matrix Amat## [1] 2 2dim( Bmat ) # The dimensions of matrix Bmat## [1] 2 3t(Bmat) # The transpose of matrix Bmat## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 10

## [2,] 2 -20

## [3,] -3 30-2 * Bmat # Multiply each element by ascalar## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] -2 -4 6

## [2,] -20 40 -60Multiplication of conformable matrices requires the special function %*%:

Cmat <- Amat %*% Bmat

Cmat## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] -29 62 -93

## [2,] 42 -76 114Multiplying non-conformable matrices produces an error:

Bmat %*% Amat # This will fail!Powers of matrices are produced by repeatedly using %*%:

Amat^2 # Each *element* of Cmat is squared## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 9

## [2,] 4 16Amat %*% Amat # Correct way to compute Cmat squared## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] -5 -15

## [2,] 10 10The usual multiplication operator used in R * is for multiplication of scalars, not matrices:

Amat * Bmat # FAILS!!The * operator can also be used for multiplying the corresponding elements of matrices of the same size:

Bmat * Cmat## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] -29 124 279

## [2,] 420 1520 3420The diagonal elements of matrices are extracted using diag():

diag(Cmat)## [1] -29 -76diag(Bmat) # diag even works for non-square matrices## [1] 1 -20diag() can also be used to create diagonal matrices:

diag( c(1,-1,2) )## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 1 0 0

## [2,] 0 -1 0

## [3,] 0 0 2In addition, diag() can be used to create identity matrices easily, in two ways:

diag( 3 ) # Creates the 3x3 identity matrix## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 1 0 0

## [2,] 0 1 0

## [3,] 0 0 1diag( nrow=3 ) # Creates the 3x3 identity matrix## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 1 0 0

## [2,] 0 1 0

## [3,] 0 0 1To determine if a square matrix is singular or not, compute the determinant using det():

det(Amat)## [1] 10Dmat <- t(Bmat) %*% Bmat; Dmat## [,1] [,2] [,3]

## [1,] 101 -198 297

## [2,] -198 404 -606

## [3,] 297 -606 909det(Dmat) # Zero to computer precision## [1] 0Zero determinants indicate singular matrices without inverses. (Near-zero determinants indicate near-singular matrices for which inverses may be difficult to compute.) The inverse of a non-singular matrix is found using solve():

Amat.inv <- solve(Amat)

Amat.inv## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 0.4 0.3

## [2,] -0.2 0.1Amat.inv %*% Amat## [,1] [,2]

## [1,] 1 -2.220446e-16

## [2,] 0 1.000000e+00However, an error is returned if the matrix is singular:

solve(Dmat) # Not possible: Dmat is singularThe use of solve() to find the inverse is related to the use of solve() in solving matrix equations of the form \(\text{A}\vec{x} = \vec{b}\) where \(\text{A}\) is a square matrix, and the vector \(\vec{x}\) unknown. For example:

bvec <- matrix( c(1,-3), ncol=1); bvec## [,1]

## [1,] 1

## [2,] -3xvec <- solve(Amat, bvec); xvec # Amat plays the role of matrix A## [,1]

## [1,] -0.5

## [2,] -0.5To check the solution:

Amat %*% xvec## [,1]

## [1,] 1

## [2,] -3This use of solve() also works if bvec is defined without using matrix(). However, the the solution returned by solve() in that case is not a matrix either:

bvec <- c(1, -3); x.vec <- solve(Amat, bvec); x.vec## [1] -0.5 -0.5is.matrix(x.vec)## [1] FALSEis.vector(x.vec)## [1] TRUE7 Where to now?

There are plenty of books and website about R if you need more help. Here are some options:

- Dalgaard’s Introductory Statistics with R is an gentle introduction to using R for basic statistics.

- Maindonald & Braun’s Data Analysis and Graphics Using R introduces R and covers a variety of statistical techniques.

- Venables & Ripley’s Modern Applied Statistics with S is an authoritative book discussing the implementation of a variety of statistical techniques in R and the closely related commercial program S-Plus.

This section is intended to extend your knowledge of R. While the previous section had a brief overview of what R can do this section will have more in-depth tutorials for commands that are often used in R. It should be useful as a reference if you are ever stuck with anything in the R tutorials and course work.

7.1 Accessing a library

Typing library(package-name) will load the library so that you can use the functions within it (with package-name replaced with the actual name of the library). For example library(DAAG) will load the DAAG library, if it has been installed.

Some packages used in the knitr textbook are already installed, however, some may not be. If, for example, you type library(DAAG) and get the error message Error in library(DAAG) : there is no package called 'DAAG' then you need to install the library first with install.packages("DAAG"). Keep in mind that the name of the package must be in quotation marks for install.packages() unlike library() which doesn’t require them (but still works with them).

Once a library is loaded you can access all the functions within that library. This isn’t that useful if you don’t actually know what the functions in the library are and what they do. Typing help(DAAG) or ?DAAG will bring up a description of what DAAG does on the Help tab (bottom right hand pane of the RStudio interface). Typing library(help="DAAG") will bring up the documentation for the DAAG library in a table in the top left pane of the RStudio interface.

When using a new package the 3 steps are:

1. install.packages("name")

2. library(name)

3. help(name) or ?(name) and/or library(help="name")

Step 1 is not necessary if the library has already been installed on your computer from a previous R session and step 3 is not necessary if you know the name of the function you want to use is and how to use it.

7.2 Creating a data frame

A data frame is a collection of information such as numbers, factors and dates. Each column of a data frame contains the same type of information. It is helpful to imagine a data frame as an Excel spread sheet.

In the code chunk below (Table 1), a vector called name was constructed using the concatonate command, c. This vector contains the names of 5 people. A vector containing their gender and a vector containing their age was also created. These 3 variables were joined together using data.frame with each variable becoming a column of the data frame. The data frame was called info and can be printed by typing info into R.

Table 1: Example Data Entry

name <- c("John","Bob","Anne","Rob","Mary")

gender <- c("M","M","F","M","F")

age <- c(23,43,32,54,27)

info <- data.frame(name, gender, age)

info## name gender age

## 1 John M 23

## 2 Bob M 43

## 3 Anne F 32

## 4 Rob M 54

## 5 Mary F 277.2.1 Accessing data in a data frame

Data can now be accessed from the data frame info. If you wanted all the ages you could get it by typing info$age or info[,3] into the command line. info$age indicates all entries from the age column and info[,3] indicates all rows (this is done by leaving it blank) from the third column. If only the first age was required it would be obtained withinfo$age[1] or info[1,3]. When using the second method to access information it is always the row number followed by the column number (dataframename[row,column]).

If you want to look at your data frame you can do it with the command View(info) (note the capital V in View). You will see that it displays the information in a format similar to Excel. You can also view your data frame in this format by finding the info variable in the global environment in the top right of RStudio and clicking on it.

7.2.2 Opening an excel document as a data frame

Data can also be entered into excel then opened in R. Enter the same data in excel then save as a .csv as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Data to enter into excel and saving as a .csv

Figure 1: Data to enter into excel and saving as a .csv

The following code chunk is used to open the above csv file in R. Don’t forget to replace the directory name dirc with your directory location.

dirc <- "~/OneDrive - University of the Sunshine Coast/Courses/ENG330/ENG330_ebook" #Replace with your directory

fname <- "dataframe.csv" #Replace with your filename

csvinfo <- read.csv(paste(dirc,fname,sep="/"))One thing to remember when creating an excel document is that all data in a column is the same type (number, string, date, etc.) For example, if you obtain data from a website it can have meta-data at the bottom. If this shares a column with numbers it will make R read the numbers as a string. It is usually best to delete this data before saving the spread sheet as a csv file. If there is text above the data, like the headings in the example, R will usually register this as the heading and will not change the data type. If R does not recognise the header, you can force it to by including the argument header = TRUE in the read.csv command.

7.2.3 Adding titles to a data frame

The data frame created at the beginning of this section used the names of the vectors as column names. This data frame is recreated below (Table 2) only without these vector names. It leads to some awkward titles.

Table 2: Example Data Frame

info2 <- data.frame(c("John","Bob","Anne","Rob","Mary"), c("M","M","F","M","F"), c(23,43,32,54,27))

info2## c..John....Bob....Anne....Rob....Mary.. c..M....M....F....M....F..

## 1 John M

## 2 Bob M

## 3 Anne F

## 4 Rob M

## 5 Mary F

## c.23..43..32..54..27.

## 1 23

## 2 43

## 3 32

## 4 54

## 5 27Proper column names can be created using the names() function (Table 3).

Table 3: Incorporating Column Names

names(info2) <- c("Name", "Gender", "Age")

info2## Name Gender Age

## 1 John M 23

## 2 Bob M 43

## 3 Anne F 32

## 4 Rob M 54

## 5 Mary F 277.2.4 Adding new columns to a data frame

We can add additional columns to a data frame. For example, the following code adds the grades of the people in the previous data frame.

grade <- c(68,78,74,59,70)

#All we need to do is assign the new values to the data frame with the <- operator

info2["Grade out of 100"] <- gradeAs you can see this also lets us assign a title to the new column. It is important to do this as if we typed info2 <- grade without the name in square brackets we would overwrite the variable name containing the data frame.

7.3 Making a graph

The following code creates a data frame called hydrograph which contains flow rate (in cumecs) and time (in hours). To plot these data the plot(hydrograph) command is used (Figure 2).

time <- seq(0,114,6) #Makes a sequence of 0 to 114 in steps of 6

flow <- c(0,21,256,831,1233,1016,502,182,71,31,15,8,5,3,2,1,1,1,0,0)

#these are the flow data for each time step

hydrograph <- data.frame(time, flow)

plot(hydrograph)

Figure 2: Plot Example

7.3.1 Adding labels

We have our graph but it isn’t very neat. To give the viewer more information we could add a title and axis labels (Figure 3).

plot(hydrograph, main="Hydrograph", xlab="Time (hours)", ylab="Flow (cumecs)")

Figure 3: Plot example with labels.

main= is used to add a title and xlab= and ylab= add a title to the x-axis and y axis respectively. These labels are strings and are therefore enclosed in double quotation marks.

7.3.2 Multiple graphs on one plot

Multiple data sets can be plotted on the same graph. Our current graph represents the inflow into a river over time during a storm. To plot the outflow on the river on the same graph, the points function is used (Figure 4).

#Creates a new data frame containing outflow data

plot(hydrograph)

out <- c(0,0,0.58,27.7,213.9,579.7,769.6,651,459.9,319.1,226.45,165.5,124.5,96,75.7,60.7,49.4,40.9,34.2,28.9)

outflow <- data.frame(time, out)

points(outflow)

Figure 4: Plot Example with Additional points.

Note that when running the above code through the command line, the inflow and outflow were not plotted at the same time, rather the inflow is plotted and the outflow is added to it. New data can be added to the last plot made.

7.3.3 Graph formatting

Now the graph contains both the inflow and outflow hydrograph. However, both have the same symbol and colour so it’s difficult to tell them apart. If we recreate the graph using lines instead of points we should be able to tell them apart (Figure 5). We can also make each line a different colour.

plot(hydrograph, type="l", col="red", main="Hydrograph", xlab="Time (hours)", ylab="Flow (cumecs)")

#Can't use plot(outflow) as that will create a new graph. lines(outflow) specifies that a line graph of outflow is to be added to the original graph

#type="l" indicates the plot will be a lines graph and col= controls the line colour

lines(outflow, col="blue")

Figure 5: Hydrograph with lines for inflow and outflow

The graph looks a lot better but there is still no way to know which line is inflow and outflow. Adding a legend is the solution to determine inflow from outflow (Figure 6)

plot(hydrograph, type="l", col="red", main="Hydrograph", xlab="Time (hours)", ylab="Flow (cumecs)")

lines(outflow, col="blue")

legend("topright", c("Inflow", "Outflow"), lty=c(1,1), col=c("red", "blue"), bty="n", cex=.75)

Figure 6: Hydrograph with a Legend

7.4 Logical operators

Logical operators test if a statement is true. They can then take an action based on whether the action is true or false. In R, = is similar to <-, it is used to assign something to a variable. R uses == to test if 2 things are equal.

x <- 1

x==1## [1] TRUEx==2## [1] FALSEThe above comparisons print TRUE followed by FALSE. The same comparison can be done with a vector of numbers.

x==c(1,3,6,1)## [1] TRUE FALSE FALSE TRUEThere are other operators which are summarised here

7.4.1 if else

If we want to do something with our TRUE or FALSE result we can create an if statement. if statements usually take the form if(test_expression){ statement }

if (x==1){

print("x = 1")

}## [1] "x = 1"The following example uses an if statement to determine whether the mean of a set of numbers is greater than the median.

num <- c(1,5,3,8,3,7,5,8,2)

if (mean(num)>median(num)){

print("The mean is greater than the median")

}The above code didn’t print the message as the mean was not greater than the median. If we want an alternate message to be printed we can use an else statement.

if (mean(num)>median(num)){

print("The mean is greater than the median")

} else {

print("The mean is not greater than the median")

}## [1] "The mean is not greater than the median"We can also create a statement with multiple results by combining ‘else’ and ‘if’.

if (mean(num)>median(num)){

print("The mean is greater than the median")

} else if (mean(num)<median(num)){

print("The mean is less than the median")

} else {

print("the mean is equal to the median")

}## [1] "The mean is less than the median"TRUE or FALSE can also be used to determine if values should be printed.

y <- 5

y[TRUE]## [1] 5y[FALSE]## numeric(0)TorF <- num==3 #Assigns the TRUE and FALSE values from the logical test to the num vector (created in a previous chunk)

TorF## [1] FALSE FALSE TRUE FALSE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSEnum[TorF] #This will print only the numbers in the vector with true (which should all be 3)## [1] 3 37.5 Creating a loop

Loops are useful when we need to perform the same operation multiple times. However, in R, loops can be avoided by the use of apply functions.

An example of the use of a loop is performing an operation for every row in the column of a data frame. The table below will be used to demonstrate the use of loops. It is a data frame called ifd and contains IFD data for Coochin (if you don’t know about IFDs yet don’t worry you will soon. This is just used here as a demonstration).

## Dur (mins) 1 year 2 years 5 years 10 years 20 years 50 years 100 years

## 1 5 125.00 159.00 196.00 217.00 247.00 286.00 316.0

## 2 6 117.00 149.00 184.00 204.00 233.00 270.00 298.0

## 3 10 95.80 122.00 152.00 169.00 192.00 223.00 247.0

## 4 20 70.30 89.70 112.00 124.00 142.00 165.00 182.0

## 5 30 57.40 73.30 91.40 102.00 117.00 136.00 150.0

## 6 60 38.80 49.70 62.80 70.50 81.00 94.80 105.0

## 7 120 24.80 32.20 41.60 47.30 54.90 65.00 73.0

## 8 180 18.80 24.50 32.30 37.10 43.50 52.00 58.7

## 9 360 11.70 15.40 21.00 24.50 29.10 35.50 40.5

## 10 720 7.40 9.87 13.80 16.40 19.70 24.30 28.0

## 11 1440 4.92 6.58 9.30 11.10 13.40 16.60 19.2

## 12 2880 3.31 4.42 6.25 7.44 8.98 11.10 12.9

## 13 4320 2.51 3.37 4.79 5.72 6.93 8.62 10.0If we want the rainfall depth for a duration of 180 minutes and an ARI of 5 years we can use a loop to find it.

ARI <- "5 years"

dur <- 180First we want to determine which row in ifd matches our duration of 180 minutes. We could do this using if statements.

if (dur==ifd[1,1]){print(1)}

if (dur==ifd[2,1]){print(2)}

if (dur==ifd[3,1]){print(3)}

if (dur==ifd[4,1]){print(4)}

if (dur==ifd[5,1]){print(5)}

if (dur==ifd[6,1]){print(6)}

if (dur==ifd[7,1]){print(7)}

if (dur==ifd[8,1]){print(8)}## [1] 8if (dur==ifd[9,1]){print(9)}

if (dur==ifd[10,1]){print(10)}

if (dur==ifd[11,1]){print(11)}

if (dur==ifd[12,1]){print(12)}

if (dur==ifd[13,1]){print(13)}The code above tests if the durations in each row matches the duration of 180 and then prints the row number if the duration matches (in this case row 8). However, it is impractical to do a logical test for each row. This is where the for loop comes in handy. The much smaller code below does the same thing as the code above.

for (i in 1:nrow(ifd)){

if (dur==ifd[i,1]){rn_dur=i}

}In the code i is a assigned a number that changes with each loop of the code. The in 1:nrow(ifd) code states that i will start at 1 and increase until it equals the number of rows (nrow(ifd)). Thus is will perform the if loop 13 times and print the row with the matching duration.

The second step is to get the ARI names which can be obtained with colnames(ifd) and find which column shares its name with the 5 year ARI.

names <- colnames(ifd)

for (i in 1:length(names)){

if (ARI==names[i]){cn=i}

}We now have the row and column number and can use them to get the rainfall.

ifd[rn_dur,cn]## [1] 32.3Like most things in R, the above can be simplified to just a couple of lines of code.

cn<-which(colnames(ifd)==ARI)

rn_dur<-which(ifd$`Dur (mins)`==dur)

ifd[rn_dur,cn]## [1] 32.37.6 Handling dates in R

Dates and times are always a challenge in any programming language, because of the many different ways in which they can be formatted. In the following code, handling dates is explored.

The following code assigns four dates (entered as strings as they enclosed in quotation marks) to a vector date. It is worth noting that these technically aren’t dates yet but characters. This is determined by running the class command.

date <- c("16/3/2012", "17/3/2012", "18/3/2012", "19/3/2012")

class(date)## [1] "character"The as.Date() function is used to turn the characters into dates. The format of the date is also required. In this example the first date "16/3/2012" is has the format of the day followed by the month followed by the year. In R, this format is represented by "%d/%m/%Y" with a lower-case d for day and m for month and an upper-case Y for year. The upper-case Y is used when the year is represented by four digits (I.e.. 2012). If only two digits are used (I.e.. 12) a lower case, y is used.

date <- as.Date(date, "%d/%m/%Y")

date## [1] "2012-03-16" "2012-03-17" "2012-03-18" "2012-03-19"class(date)## [1] "Date"7.6.1 Dates with time

What if the dates also contain times? In the following code times are included with the previous dates.

date <- c("16/3/2012 10:00:00", "17/3/2012 10:00:00", "18/3/2012 10:00:00", "19/3/2012 10:00:00")The same date format used previously is used and the time format added: "%H:%M:%S". Note that the letters for hours, minutes and seconds are all upper-case. Also note that the characters are separated by : instead of /. It is important that the symbols in the format match the symbols in the date (if the date was 16-3-2012 then dashes would be used instead of forward slashes). The full formatting will look like "%d/%m/%Y H:%M:%S". as.Date can only work with dates not time. The functions as.POSIXct() or as.POSIXlt() are used when time is included.

date <- as.POSIXct(date, format="%d/%m/%Y %H:%M:%S")

date## [1] "2012-03-16 10:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-17 10:00:00 AEST"

## [3] "2012-03-18 10:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-19 10:00:00 AEST"You might have noticed that a time zone has been added to the values. This can be set but if it isn’t it will default to the time zone of your system.

We now have four dates with time. Combining these dates with hypothetical rainfall values we can create a graph of rainfall over the four days (Figure 7).

rain <- c(12,35,8,0)

plot(date, rain)

Figure 7: Example plot of Rainfall data

We can also use the zoo() function to combine the rainfall values with the dates. This package is designed to create timeseries data and can multiple variables for one date.

This package will be covered in more detail in the section on flood frequency analysis.

library(zoo)

raindata <- zoo(rain, date)7.6.2 Creating dates from sequences

If we have a start date and an end date and don’t want to enter all the other dates in between we can use the seq() function to produce a list of dates from the start to finish date.

#If we wanted all the dates from the 10th of March to the 25th of March we would use:

stdate <- as.Date("10/3/2012", "%d/%m/%Y")

enddate <- as.Date("25/3/2012", "%d/%m/%Y")

seq(stdate, enddate, by="day")## [1] "2012-03-10" "2012-03-11" "2012-03-12" "2012-03-13" "2012-03-14"

## [6] "2012-03-15" "2012-03-16" "2012-03-17" "2012-03-18" "2012-03-19"

## [11] "2012-03-20" "2012-03-21" "2012-03-22" "2012-03-23" "2012-03-24"

## [16] "2012-03-25"#If we wanted every hour in the 10th of March we would use:

sttime <- as.POSIXct("10/3/2012 00:00:00", format="%d/%m/%Y %H:%M:%S")

endtime <- as.POSIXct("10/3/2012 23:00:00", format="%d/%m/%Y %H:%M:%S")

seq(sttime, endtime, by="hour")## [1] "2012-03-10 00:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 01:00:00 AEST"

## [3] "2012-03-10 02:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 03:00:00 AEST"

## [5] "2012-03-10 04:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 05:00:00 AEST"

## [7] "2012-03-10 06:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 07:00:00 AEST"

## [9] "2012-03-10 08:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 09:00:00 AEST"

## [11] "2012-03-10 10:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 11:00:00 AEST"

## [13] "2012-03-10 12:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 13:00:00 AEST"

## [15] "2012-03-10 14:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 15:00:00 AEST"

## [17] "2012-03-10 16:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 17:00:00 AEST"

## [19] "2012-03-10 18:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 19:00:00 AEST"

## [21] "2012-03-10 20:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 21:00:00 AEST"

## [23] "2012-03-10 22:00:00 AEST" "2012-03-10 23:00:00 AEST"7.6.3 Organising data into dates

Data we obtain from sites like the BoM are not always in the neat format of the data we have been working with so far. The following example demonstrates the case where the year is missing from the date, and the times are in a separate column.

## dates times values

## 1 10/3 00:30 12

## 2 11/3 08:00 43

## 3 12/3 15:30 45

## 4 13/3 20:00 67

## 5 14/3 17:00 123

## 6 15/3 16:30 156

## 7 16/3 05:00 145

## 8 17/3 09:00 121

## 9 18/3 12:30 85

## 10 19/3 17:00 42The data frame Data contains values for ten different times for the year 2016. We want to organise the dates and time into one string that we can convert to a date. The dates do not contain the year. We can add the year to the end by converting the data to a string. Below is an example using just the first date, followed by an example of a loop for all the dates.

date1 <- toString(Data[,1])

date1full <- paste(toString(Data[,1]), collapse="/2016")

date1full## [1] "10/3, 11/3, 12/3, 13/3, 14/3, 15/3, 16/3, 17/3, 18/3, 19/3"#A loop will be created to do the same for all the dates

datefull <- c() #An empty list is created to store the combined dates

for (i in 1:nrow(Data)){

datefull <- c(datefull, paste(c(toString(Data[i,1]), "2016"), collapse="/"))

}

#We will now repeat the process above, adding the times from column 2 to the dates

for (i in 1:nrow(Data)){

datefull[i] <- paste(c(datefull[i], toString(Data[i,2])), collapse=" ")

}We now have a list of dates in the correct format. All that’s left to do is convert the characters to dates with as.POSIXct() and add it to the data frame.

#The dates don't contain minutes so '%H:%M' is used instead of '%H:%M:%S'

newdates <- as.POSIXct(datefull, format="%d/%m/%Y %H:%M")

Data["Date & time"] <- newdates

Data## dates times values Date & time

## 1 10/3 00:30 12 2016-03-10 00:30:00

## 2 11/3 08:00 43 2016-03-11 08:00:00

## 3 12/3 15:30 45 2016-03-12 15:30:00

## 4 13/3 20:00 67 2016-03-13 20:00:00

## 5 14/3 17:00 123 2016-03-14 17:00:00

## 6 15/3 16:30 156 2016-03-15 16:30:00

## 7 16/3 05:00 145 2016-03-16 05:00:00

## 8 17/3 09:00 121 2016-03-17 09:00:00

## 9 18/3 12:30 85 2016-03-18 12:30:00

## 10 19/3 17:00 42 2016-03-19 17:00:00We can now create graphs with these data. The ggplot2 library is used to construct Figure 8. This is a powerful library that provides a lot of flexibility for constructing graphics. the gg refers to the grammer of graphics. Work through the following code and try and work out how this library enables you to build your graphics in a modular way.

library(ggplot2)

ggplot(Data,aes(x=Data[,4],y=values))+ geom_bar(stat="identity",colour="blue",fill="blue",width=0.1)+labs(x="Date-Time",y="Rainfall (mm)")

Figure 8: Example plot of a timeseries of Rainfall data using the ggplot2 library.

8 Tutorial 1 - Hydrologic Data in R

There are several packages available in R that provide access to hydrologic data. In this tutorial we will explore the package DAAG.

Typing the command library(help="DAAG") will bring up a tab in the top left-hand panel of RStudio called “Documentation for package ‘DAAG’”. The information included is an index of all the data-sets available. The data-set of most interest to us is bomregions2012. The following steps are required to access these data and have a look at how it is structured:

library(DAAG) #if the package is already installed. If not, type install.packages("DAAG") first## Warning: package 'DAAG' was built under R version 3.5.2data(bomregions2012)

# to explore the underlying structure of the data enter the following commands:

str(bomregions2012)## 'data.frame': 113 obs. of 22 variables:

## $ Year : num 1900 1901 1902 1903 1904 ...

## $ eastAVt : num NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ seAVt : num NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ southAVt : num NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ swAVt : num NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ westAVt : num NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ northAVt : num NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ mdbAVt : num NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ auAVt : num NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ eastRain : num 453 531 330 728 596 ...

## $ seRain : num 655 568 462 688 607 ...

## $ southRain: num 375 322 288 431 395 ...

## $ swRain : num 790 583 567 777 769 ...

## $ westRain : num 384 301 344 361 403 ...

## $ northRain: num 369 478 336 607 613 ...

## $ mdbRain : num 419 372 258 535 457 ...

## $ auRain : num 373 407 314 527 513 ...

## $ SOI : num -5.55 0.992 0.458 4.933 4.35 ...

## $ co2mlo : num NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA NA ...

## $ co2law : num 296 296 296 297 297 ...

## $ CO2 : num 296 297 297 297 298 ...

## $ sunspot : num 9.5 2.7 5 24.4 42 63.5 53.8 62 48.5 43.9 ...summary(bomregions2012)## Year eastAVt seAVt southAVt

## Min. :1900 Min. :19.36 Min. :13.68 Min. :17.52

## 1st Qu.:1928 1st Qu.:20.12 1st Qu.:14.31 1st Qu.:18.18

## Median :1956 Median :20.41 Median :14.61 Median :18.52

## Mean :1956 Mean :20.43 Mean :14.66 Mean :18.54

## 3rd Qu.:1984 3rd Qu.:20.75 3rd Qu.:15.04 3rd Qu.:18.86

## Max. :2012 Max. :21.63 Max. :15.95 Max. :19.64

## NA's :10 NA's :10 NA's :10

## swAVt westAVt northAVt mdbAVt

## Min. :15.06 Min. :21.24 Min. :23.46 Min. :16.40

## 1st Qu.:15.80 1st Qu.:22.04 1st Qu.:24.27 1st Qu.:17.27

## Median :16.25 Median :22.39 Median :24.53 Median :17.63

## Mean :16.21 Mean :22.38 Mean :24.58 Mean :17.65

## 3rd Qu.:16.65 3rd Qu.:22.68 3rd Qu.:24.93 3rd Qu.:17.95

## Max. :17.44 Max. :23.40 Max. :25.88 Max. :19.04

## NA's :10 NA's :10 NA's :10 NA's :10

## auAVt eastRain seRain southRain

## Min. :20.65 Min. : 330.5 Min. :367.2 Min. :241.2

## 1st Qu.:21.41 1st Qu.: 516.0 1st Qu.:566.7 1st Qu.:339.9

## Median :21.68 Median : 603.4 Median :627.8 Median :371.6

## Mean :21.72 Mean : 611.4 Mean :627.8 Mean :384.6

## 3rd Qu.:22.00 3rd Qu.: 684.3 3rd Qu.:688.1 3rd Qu.:431.2

## Max. :22.84 Max. :1028.4 Max. :916.8 Max. :598.1

## NA's :10

## swRain westRain northRain mdbRain

## Min. : 394.6 Min. :168.0 Min. :316.6 Min. :258.1

## 1st Qu.: 612.8 1st Qu.:287.6 1st Qu.:432.1 1st Qu.:393.2

## Median : 681.0 Median :338.4 Median :509.1 Median :471.6

## Mean : 678.9 Mean :343.1 Mean :518.2 Mean :471.4

## 3rd Qu.: 742.6 3rd Qu.:383.9 3rd Qu.:576.1 3rd Qu.:541.1

## Max. :1037.0 Max. :604.2 Max. :905.6 Max. :808.6

##

## auRain SOI co2mlo co2law

## Min. :314.5 Min. :-20.0083 Min. :316.0 Min. :295.8

## 1st Qu.:398.0 1st Qu.: -3.6250 1st Qu.:328.0 1st Qu.:302.9

## Median :444.9 Median : 0.5250 Median :346.7 Median :310.1

## Mean :457.1 Mean : 0.1936 Mean :349.0 Mean :310.4

## 3rd Qu.:500.2 3rd Qu.: 4.3500 3rd Qu.:367.9 3rd Qu.:315.2

## Max. :759.6 Max. : 20.7917 Max. :393.8 Max. :333.7

## NA's :59 NA's :34

## CO2 sunspot

## Min. :296.3 Min. : 1.40

## 1st Qu.:306.8 1st Qu.: 17.50

## Median :314.1 Median : 47.40

## Mean :326.7 Mean : 59.13

## 3rd Qu.:344.6 3rd Qu.: 92.60

## Max. :393.8 Max. :190.20

## To find out what the variables are in bomregions2012 data, type ?bomregions2012 at the command prompt. This will bring up the R Documentation for this data-set under the Help Tab in the bottom right panel of RStudio. I encourage you to read this documentation and explore (and implement) the examples provided at the end of the documentation (Copy and paste the examples directly into the Console, at the command prompt). These examples are quite complicated, so I wouldn’t expect you to understand what is going on. For now, just marvel at the power of R in producing these plots with just a few commands!

We will take a simpler approach to plotting the data. When the str() command was entered the first line that was printed in the Console window was 'data.frame': 113 obs. of 22 variables:. This tells us that the data is stored in a data.frame with 113 rows and 22 columns.

Typing the command colnames(bomregions2012) lists the following column names:

## [1] "Year" "eastAVt" "seAVt" "southAVt" "swAVt"

## [6] "westAVt" "northAVt" "mdbAVt" "auAVt" "eastRain"

## [11] "seRain" "southRain" "swRain" "westRain" "northRain"

## [16] "mdbRain" "auRain" "SOI" "co2mlo" "co2law"

## [21] "CO2" "sunspot"8.1 Accessing data via column names and row numbers

There are several ways to access data in a particular column. We can use the data-set name (ie. bomregions2012), followed by the dollar sign $, followed by the name of the column (eg. swRain), followed by square brackets []. We can include a number inside the brackets to return a specific record. For example to return the value in the fourth row of the swRain column, you would type: bomregions2012$swRain[4]. Give it a try at the command line. The result returned should be 777.12.

You can also access a range of numbers. For example the first three numbers, can be accessed using bomregions2012$swRain[1:3]. If you want to access records that are not continuous (eg. you might want to see the first, fifth and seventh records because you know they were very big rainfall years), you use the concatenate command c(), inside the square brackets: bomregions2012$swRain[c(1,5,7)]. To access every fourth number (eg. we might want only the leap years), you can use the sequence seq(1, nrow(bomregions2012), by=4). In this example, the nrow(bomregions2012) command is returning the number of rows in the bomregions2012 data-set: 113.

8.2 Accessing data via column and row numbers (two dimensional notation)

It can be a bit cumbersome to type in the names of the columns each time, so to shorten the command we can use the index of the column/s and the row/s. The 13th column contains the swRain records, so to access the fourth record, use the following command: bomregions2012[4,13]. Note the row index is first. If you paste this command into the command prompt in the console you should get the same answer as previously: 777.12.

In the same way that you can access different records (ie. rows), you can also access multiple columns. If you want to access columns 4 and 7 for all the records the command in the two dimensional notation is bomregions2012[ ,c(4,7)]. Note in this example the first index is blank. This will return all the records for that dimension (eg. all the rows).

8.3 Plot the data

To create a simple plot of the data in a single column, you simply use the plot() command, with the name of the variable to plot enclosed in (). For example to plot the Southwest Rainfall (swRain), you could enter plot(bomregions2012[,13]). What is the other notation to produce the same plot?

This is a rather boring plot, and there are lots of ways to improve it. Before exploring this, there are a few other basic plots to examine. At the command prompt, enter the following functions and observe the result in the plot window:

hist(bomregions2012[,13])boxplot(bomregions2012[,13])

In the first case a histogram is produced of the swRain and the second case is a box and whisker plot of the same data. I assume you are familiar with a histogram, but you may not have encountered a box and whisker plot previously.

The Box and Whisker plot represents the inter-quartile range (IQR) (or distance between the first and third quartiles of the data) by the ‘box’ part of the graph. The extent of the ‘whiskers’ represents the highest/lowest value within 1.5 times the IQR. Any data outside +/- 1.5 times the IQR are considered as outliers and plotted as points.

You may have notices that the hist command produced axis labels and a title from the data, however the boxplot only had numbers on the y-axis. To include these labels we can pass the required arguments when the command is issued.

boxplot(bomregions2012[,13],main="Box Plot of rainfall from South Western Australia",ylab="Annual Rainfall (mm)") There are many other arguments that can be issued to improve this graph. Entering

There are many other arguments that can be issued to improve this graph. Entering ?boxplot at the command prompt will bring up information and examples under the Help tab in the bottom right panel of RStudio.

8.3.1 Scatter plot

The scatter plot displays the relationship between two (or more) variables. There are many ways to create scatter plots, but if two variables (eg. x and y) are passed to the plot() function, this will create a scatter plot. For example to plot the relationship between the SOI (Southern Oscillation Index) and the Eastern Australian region rainfall the following function is entered at the command prompt: plot(bomregions2012$SOI,bomregions2012$eastRain). The following plot is produced using this command with some additional arguments. See if you can reproduce this plot.

Another useful technique for exploring the relationship between many variables can be found in the lattice library. Within this library is the function splom that plots the relationships between many variables using only one command. The following command plots a matrix of scatter plots for the data in the eastRain, seRain, southRain, SOI, co2mlo, sunspot columns.

splom(bomregions2012[,c(10,11,12,18,19,22)],varname.cex=2, axis.text.cex=1.3) #plots matrix of scatter plots for the data in columns 10,11,12,18,19 and 22.

Post on the discussion board what you think the arguments varname.cex=2, axis.text.cex=1.3 are for.

8.4 More Australian Hydrology Data

The library hydrostats also hydrology related functions as well as two Australian streamflow data-sets. Entering library(help="hydrostats") at the command line will display information about this package in a tab in the top left panel of RStudio. Enter ?hydrostats at the command line and click on the Index hyperlink at the bottom of this Help document. This will bring up another document with hyperlinks for all the functions and data sets in the hydrostats package.

Load the Cooper data-set data(Cooper). Another way that you can get an insight into data is by using the head() command. Entering head(Cooper) will return the first six records. You can control the number of records returned by using the arguement, n. For example to return the first ten records enter head(Cooper, n=10) at the command prompt. There is a similar function to return the last number of records. Can you find what this function is?

Entering the str(Cooper) command provides the information that the Cooper data-set is a data.frame with 7670 observations (records or number of rows) with two variables. The two variables are Date which is stored as a factor and Q (discharge) which is stored as a number. The data are at a daily time step (Ml/day) and therefore can be coerced into a time-series. The concept of time-series is very important in hydrology so it is important that you become familiar with creating a time-series and manipulating it to return aggregated temporal data.

Before coercing it into a time-series plot the discharge data using the following commands:

library(hydrostats) # if this library isn't available, install.packages("hydrostats is run first")## Warning: package 'hydrostats' was built under R version 3.5.2data(Cooper) #This command makes the Cooper daily discharge data available

plot(Cooper[,2]) #plots the discharge data Note on the x-axis an

Note on the x-axis an Index number is plotted. This is simply the index identifying the row number of each record. On the y-axis the label Cooper[,2] is automatically applied by R.

8.5 Time-series creation and manipulation

Working with dates is ALWAYS problematic in any programming language (even Excel). The way R interprets dates at times can be very confusing, and therefore a cause of frustration. Over the next couple of weeks I will introduce you to techniques to help alleviate this frustration (hopefully)! Once you are certain that R is reading your dates correctly, you will more than likely want to work with the data as a time-series.

There are several time-series functions and packages in R. The function ts is included in the base stats package and has three uses. Enter ?ts at the command prompt to access information about these uses.

The time-series package I find the most useful is the zoo package. We will investigate the use of this package later in the course, however the package documentation is good place to start.

For now we will use the ts.format function included in the hydrostats package. The help file for this function provides the following example to create a time-series named Cooper.

data(Cooper)

Cooper<-ts.format(Cooper)Note this is the same name as the data.frame. Now when you enter the str(Cooper), the Date now has a data type of POSIXct, indicating it is a Date-Time Class. This site provides more information on other Date-Time classes.

Now that it is a time-series object, when you enter the function plot(Cooper) (without the square brackets) you will notice that the year is now included on the x-axis, and the label Q is placed on the y-axis. This plot isn’t very attractive because the data are skewed. This can be clearly seen by using the hist(Cooper[,2]) function. This is a common characteristic of streamflow data with low flows much of the time combined with rare events that are very large. We will cover the concept of skew later in the course.

It is more usual to plot time-series data using a line, rather than points. This can be achieved easily in R by including the type="l" argument in the plot() command:

plot(Cooper,type="l",col="blue",main="Cooper Creek Daily Discharge Data (Ml/day)") #this creates a time-series line plot (colour blue) of the Cooper creek daily discharge data (Q).

grid() #"This will add gridlines to the plot at default intervals"

Plotting the time-series is usually the first step to investigating the behaviour of the data. There are other functions available in the hydrostats package to analyse these data. For example the CTF function calculates summary statistics describing cease-to-flow spell characteristics:

CTF(Cooper) #returns the cease-to-flow statistics pertaining to the Cooper creek, after it has been coerced into a time-series object.## p.CTF avg.CTF med.CTF min.CTF max.CTF

## 1 0.43103 80.63415 50 1 257The meanings of each of the headings are given in the help documentation ?CTF.

Using the data introduced in this tutorial, I encourage you to further explore the statistics you can derive from them and ways you can plot them in R. Please post the functions you have tried on the discussion board.

9 Theme 1 Module 1: The hydrologic cycle

9.1 Introduction

The decade of reduced rainfall from the mid-nineties to late 2010 and the subsequent flooding events in the summer of 2011 in Queensland provides a good example of the contrasting problems faced by engineers who do any work that intersects with the water cycle.

Understanding, monitoring and modelling the behaviour of the water cycle as it relates to the amount of water available from a dry period through to the excess water in wet times, provides the underpinning theory of hydrology.

Nearly all engineering works interact with the water cycle at some point in time (e.g. roads, buildings, dams and culverts). Calculating the volume of water to be routed through and around the structure or contained within its boundaries is the application of hydrology practice.

For the dry times, engineers involved in the water supply sector need to be able to design and manage water storages and associated infrastructure so as to provide a continuous water supply. The design criteria for water supply systems are such that water is provided with a minimum of disruption for domestic, industrial and agricultural use.

For the wet times, engineers need to be able build structures that mitigate the damage large volumes of water can cause to infrastructure, the environment and indeed life. The cost of building infrastructure to mitigate against very large rainfall events can be cost prohibitive and so society has accepted a level of risk that a flooding event will occur. This risk is quantified through probabilities of occurrence of floods of various magnitudes.

As we have seen with the Queensland Flood Commission of Inquiry, working in this area brings major responsibilities and the public can be very quick to blame the engineers for getting it wrong. Therefore it is very important to have a good grounding in the basic principles and theories.

These basic principles cover statistical techniques for understanding the frequency of events and assessing the risk of occurrences (probabilities), the components of the water cycle and how they impact on the hydrological behaviour of a region and the physical processes that govern the movement of water through and within the landscape. This course will give an introduction to these basic principles. This module will cover the basics of the hydrologic cycle: rainfall, evaporation and infiltration.

9.2 Objectives

When you have completed this module of the course you should be able to:

- Describe how a water balance is constructed and it’s application at different scales;

- Describe the key transport processes of the hydrologic cycle and their relative importance;

- Describe the main water stores that influence the water balance.

9.3 Key Principles and Elements

The key elements of the hydrologic cycle are the processes that transport water between the earth, groundwater, oceans and the atmosphere (rainfall, evapotranspiration, runoff) and the stores that detain water on the surface of the earth (dams and lakes, rivers, vegetation), beneath the earth (soil moisture and groundwater) and in the oceans.

The water balance is a key principle that underpins our understanding of the hydrologic cycle and the interactions between the stores and processes that move water between these stores.

9.4 The Hydrologic Cycle

Hydrology is an environmental science spanning the disciplines of engineering, biology, chemistry, physics, geomorphology, meteorology, geology, ecology, oceanography and, increasingly, the social environmental sciences such as planning, economics and political conflict resolution (Clifford, 2002).

The occurrence, circulation and distribution of the waters of the Earth is the foundation of the study of hydrology and embraces the physical, chemical, and biological reactions of water in natural and man-made environments. The complex nature of the hydrologic cycle is such that weather patterns, soil types, topography and other geologic factors are important components of the study of hydrology.

When dealing with the hydrologic cycle we are generally only focused on the movement of water within our region of interest. However the movement of water at the global scale is very important from the point of view of the climatic conditions that drive the regional movement of water.

Solar heating is the primary driver for the hydrologic cycle at the global scale. Solar radiation is a key input into evaporation from water (both oceans and freshwater bodies) and the land surface. The water that is evaporated enters the atmosphere as water vapour and is transported by winds around the globe. When the conditions are suitable this water vapour is condensed to form clouds. These clouds hold the moisture that will potentially fall as precipitation over the land and oceans when another set of atmospheric conditions (mainly temperature and the pressure exerted by the water vapour) are met.

Precipitation falls as rainfall, snow or hail. Once it reaches the earth surface it is stored temporarily in hollows on the surface, as soil moisture or as snow. Once all the temporary stores are filled, excess rainfall runs off into streams, rivers, lakes and man-made reservoirs or infiltrates into the soil from where it may continue to infiltrate to the groundwater store. Eventually the water in the rivers, lakes, reservoirs and groundwater makes it’s way to the oceans and is evaporated again to complete the global water cycle.

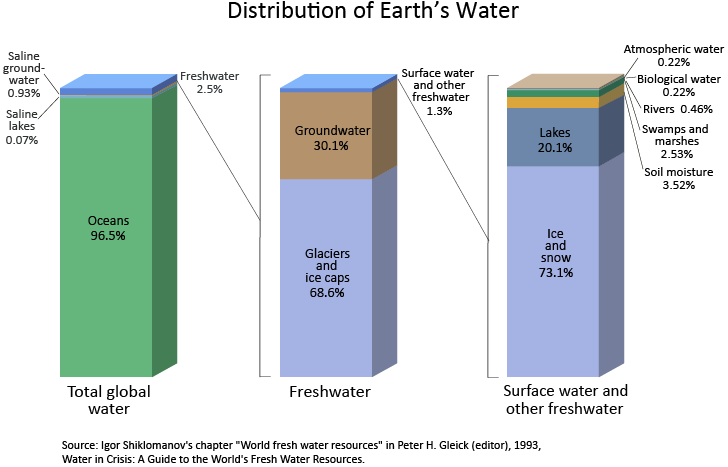

Trenberth et al. 2007 provides a representation of the global hydrological cycle (Figure 1.1.1). The values assigned to each of the main water storage units (called reservoirs in Trenberth et al. (2007) are slightly different to those provided by Ladson (2009, p 4), with the exception of soil moisture, which is different by a factor of 8 (Table 1.1). This highlights the uncertainty associated with trying to quantify the elements of the global hydrologic cycle.